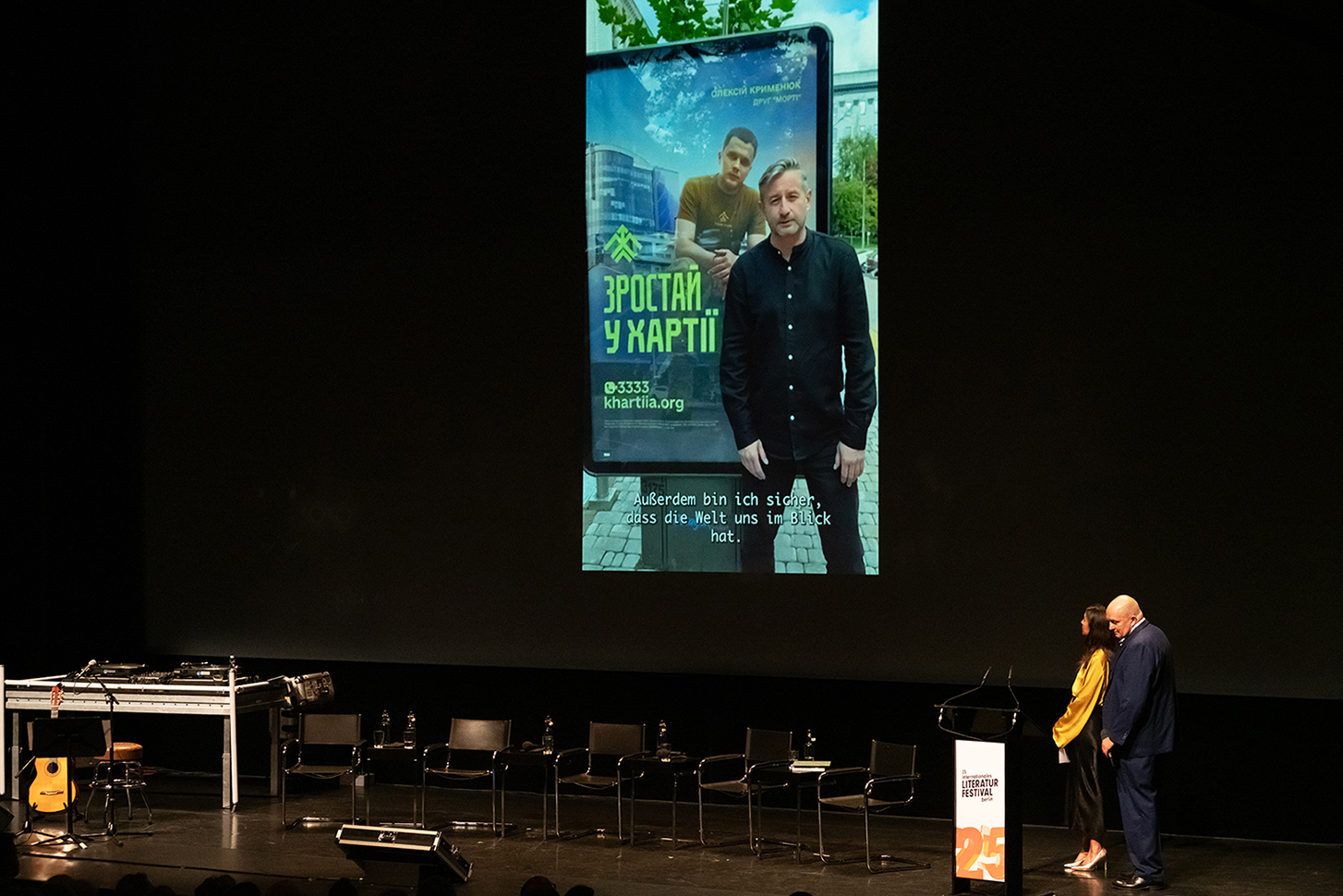

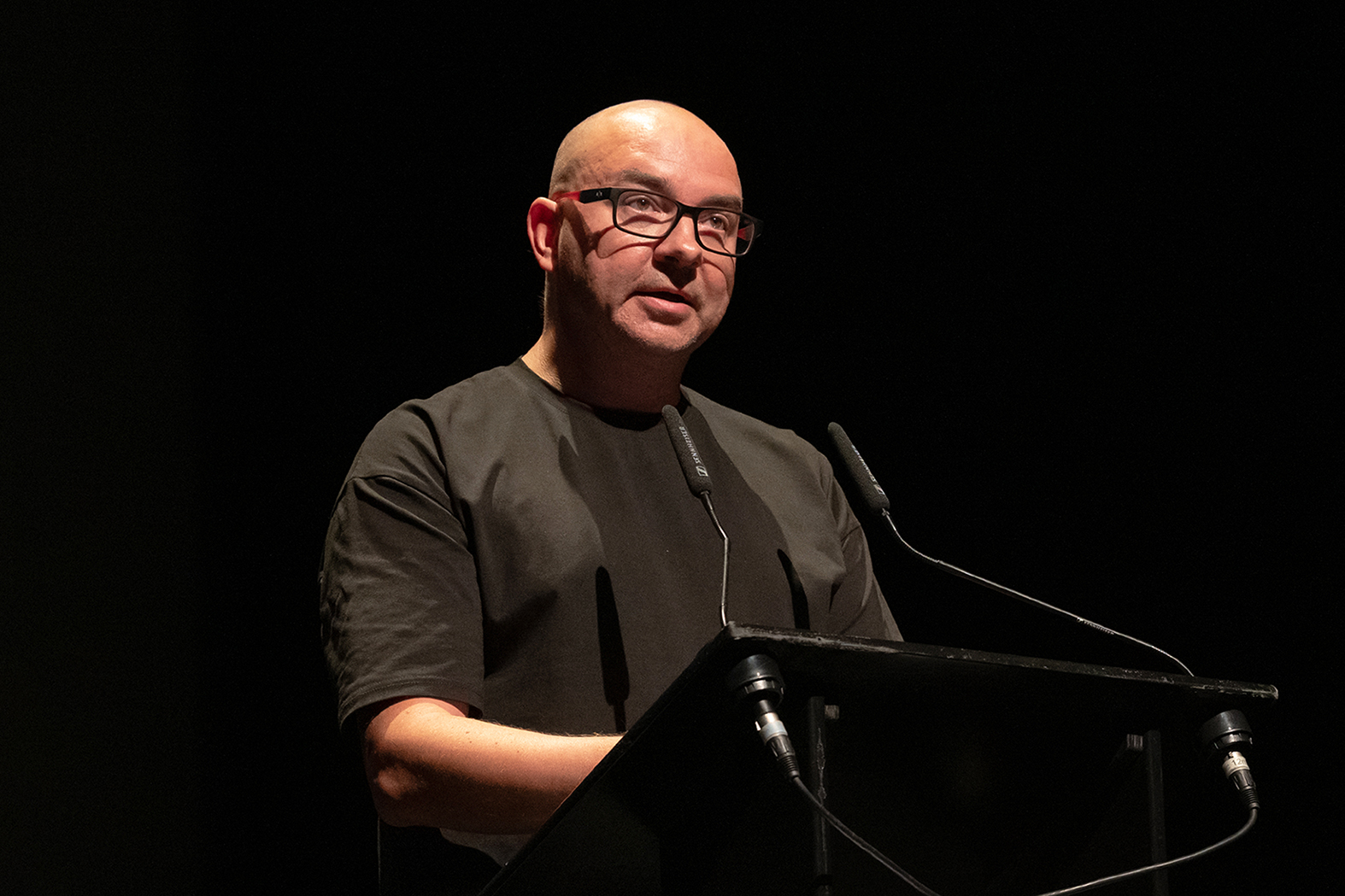

Keynote at the solidarity evening for Ukraine,

internationales literaturfestival berlin, Haus der Berliner Festspiele, 19 September 2025

For Us, the Word »Hero« Is No Longer Melodramatic

By Volodymyr Yermolenko

Photos: Erik Weiss

[Listen to the original version (in German)]

December 2022. We are in Kherson. The city was liberated by the Russian army a month ago. It had been occupied for eight months. Eight months of terror, abductions, torture chambers, and devastation. The Russians have retreated just three, four or five kilometres away to the other bank of the Dnipro.

This evening, we are meeting in the Kherson Oblast Library, which is named after Oles Honchar. Parts of the building are damaged, but it is still standing.

We are a group of Ukrainian writers and philosophers. The wind blows in from the river and, with it, we sense the proximity of the occupiers on the opposite bank. Perhaps they can see us through their »devices«. The locals advise us to stay away from the windows — Russian snipers sometimes shoot indiscriminately at civilians. Viktoria Amelina ignores this advice, steps up to the window and turns to us, waving ironically. Tanya Teren and Katya Michalizyna try in vain to stop her. But they know that such attempts are futile with Vika. She is playing with danger.

Six months later, Wiktorija will die. On 27 June 2023, a Russian missile will kill her in Kramatorsk while she is having dinner with Colombian authors in a restaurant. It is the same restaurant where we had dinner with Deniz Yücel, the spokesperson for PEN Berlin, a few months earlier in January 2023. Just a few days before the missile attack in June, Wiktorija performed some of her poetry on stage at Book Arsenal. I accompanied her on the piano. She wore a long black dress.

Wiktorija did not die immediately. The doctors fought for her life for several days. First in Kramatorsk, then in Dnipro. We tried to be with her and be there for her. Her husband, Oleksandr, and her friends. During the day, we were at the hospital; in the evening, back at the hotel, we tried to cope somehow. We made jokes, just as Wiktorija always had, and pretended that we knew nothing of the inevitable. Then the phone rang — it was Sofia, another of her friends. After that, there was only emptiness.

In November 2023, the Khontsar Library was finally destroyed by Russian shelling. A few weeks later, when my wife Tanja and I walk through Kherson, the neighbourhoods along the Dnipro River are deserted. The square in front of the library was empty and, in some places, the tails of unexploded bombs protruded from the ground. A drone flies overhead.

Now, only the two of us remain, along with the car we brought for the soldiers and the drone. It is the only moving object in this frozen, destroyed world. A world that has been deprived of its purpose. Its heartbeat has been taken away.

The absence of others

Without our dead, it will always be empty. Permanently empty. In cities on the front line, the sounds of war have become part of everyday life. Like birdsong or the roar of cars on the main roads. Mixed in with this is the sound of explosions. Are they impacts or shoot-downs? Sometimes it’s hard to tell when they’re too far away.

But the absence of sound is no less painful. A thick, immovable silence. A silence that cannot be dispelled. It’s a silence you could lean on – it has become so dense.

We hear such silence in villages that no longer exist: Kamyanka and Dovhenke in the Kharkiv Oblast, Bohorodychne and Dolyna in the Donetsk Oblast; Posad-Pokrovske in the Kherson Oblast. The dacha settlement in the village of Moshchun in the Kyiv Oblast. Villages with burned-out houses. Roofs that look like animal skeletons. Burnt, bent iron. The silence is pierced by the sound of sooty metal — the corrugated iron that covered destroyed petrol stations — rubbing against each other in a uniform, repetitive manner, as if they still have something to tell us.

In some of these villages, only five people remain out of an original population of eight hundred. In others, a few dozen remain. In some, there is no one at all.

»Hell is other people«, said Sartre. »Hell is the absence of other people«, we say. We miss their voices, their laughter, their annoying comments and their failed jokes.

People can get on our nerves; sometimes they are truly unbearable and we wish we were somewhere without them. But in this war, from time to time, we find ourselves in places where they really are no longer there – perhaps forever. Nothing is more unbearable than their absence; nothing more unbearable than this deadly silence; nothing more unbearable than lifeless things without living beings; nothing more unbearable than a geography where there are no longer any human voices. Hell is the absence of presence.

Radical evil

The Soviet Union was one of the countries that started World War II, but, unlike Nazi Germany, it did not lose the war. While 1945 marked the victory of good over evil for the Western world, for us it was the victory of one evil over another.

A few years after the war ended, Hannah Arendt published one of the most important books of the 20th century: The Origins of Totalitarianism. In it, she argues that totalitarianism is based on what she calls »radical evil«. This radical evil makes people interchangeable. Superfluous. It is the idea that people can be torn from their place and moved somewhere else. Those whose death no one should notice — because no one should have noticed their life in the first place.

Tyrannies are at their strongest when they keep everyone in fear. They achieve this by demonstrating their power over our lives and, above all, our deaths. Tyrants believe that they determine when we die. They want everyone to believe that they own our deaths.

Evil becomes confident when it is repeated. When a crime goes unpunished. Then it begins to convince everyone that its crimes are in fact punishments for the crimes of others. It wants to convince us that the victims are the perpetrators and the perpetrators are the victims. It wants its crimes to be seen as the ultimate form of justice.

Putin’s Russia is waging war not only against Ukraine. It is also waging war against reality. It is waging war against justice. It is waging war against a world in which the concepts of good and evil have meaning. A world where they are not devalued or interchanged.

Putin wants Europe to disappear — not only as a political entity, but also as a set of values. Europe, on the other hand, wants to take as few risks as possible in order to make the world safer. In contrast, Putin’s Russia is prepared to take greater risks, raising the stakes every day and making the world more dangerous.

The fear of provoking Russia only serves to provoke Russia. If you’re in a dispute with someone who’s constantly escalating the situation and you’re always avoiding confrontation, you’ll lose. However, Putin wants to destroy something even greater: Europe’s belief in itself. And so far, he has succeeded. Europe resembles a man drowning in despair. In discord.

Defiance and faith

In contrast to Václav Havel’s »The Power of the Powerless«, Europe is becoming a continent where the powerful are powerless. Why? Because there is no faith. However, faith can be found in resistance. Faith is born of the impossible. Despite the war, we are witnessing the blossoming of Ukrainian culture. How can this be? Because culture is not a superstructure; it is the structure itself. Culture helps us to survive and be ourselves. It enables us to continue pursuing and upholding fundamental human values despite the dangers. Life in spite of death. Love in spite of pain. Joy in spite of suffering. This is a culture of »spite«.

Unlike in the physical world, the spiritual world does not adhere to the law of conservation of energy. Power in the spiritual world does not result from arithmetic equations. It often appears when you least expect it.

Today, Europe is helping Ukraine, but Ukraine is also helping Europe. Ukraine is helping Europe to rediscover its purpose of resisting tyranny. This is the origin of the European Union. Europe itself was once imperialistic and knows what it means to be on the side of evil, and then to switch to the side of good. It knows what it means to be a tyrant and to overcome tyranny.

A hero is someone who stands up to someone stronger than themselves. Their belief in the impossible carries them forward. For us, the word »hero« is no longer melodramatic. It has become pragmatic. We challenge that which seems stronger than us. We gain strength by achieving what was once thought impossible. That is why we say:

Honour Ukraine. Honour the heroes.

* Volodymyr Yermolenko was born in Kyiv in 1980 and is a philosopher and essayist. He is the president of PEN Ukraine and one of the country’s most prominent intellectuals.

Opening speech by Deniz Yücel: »We Are Not Neutral«

Eine gemeinsame Veranstaltung mit

Mit freundlicher Unterstützung von