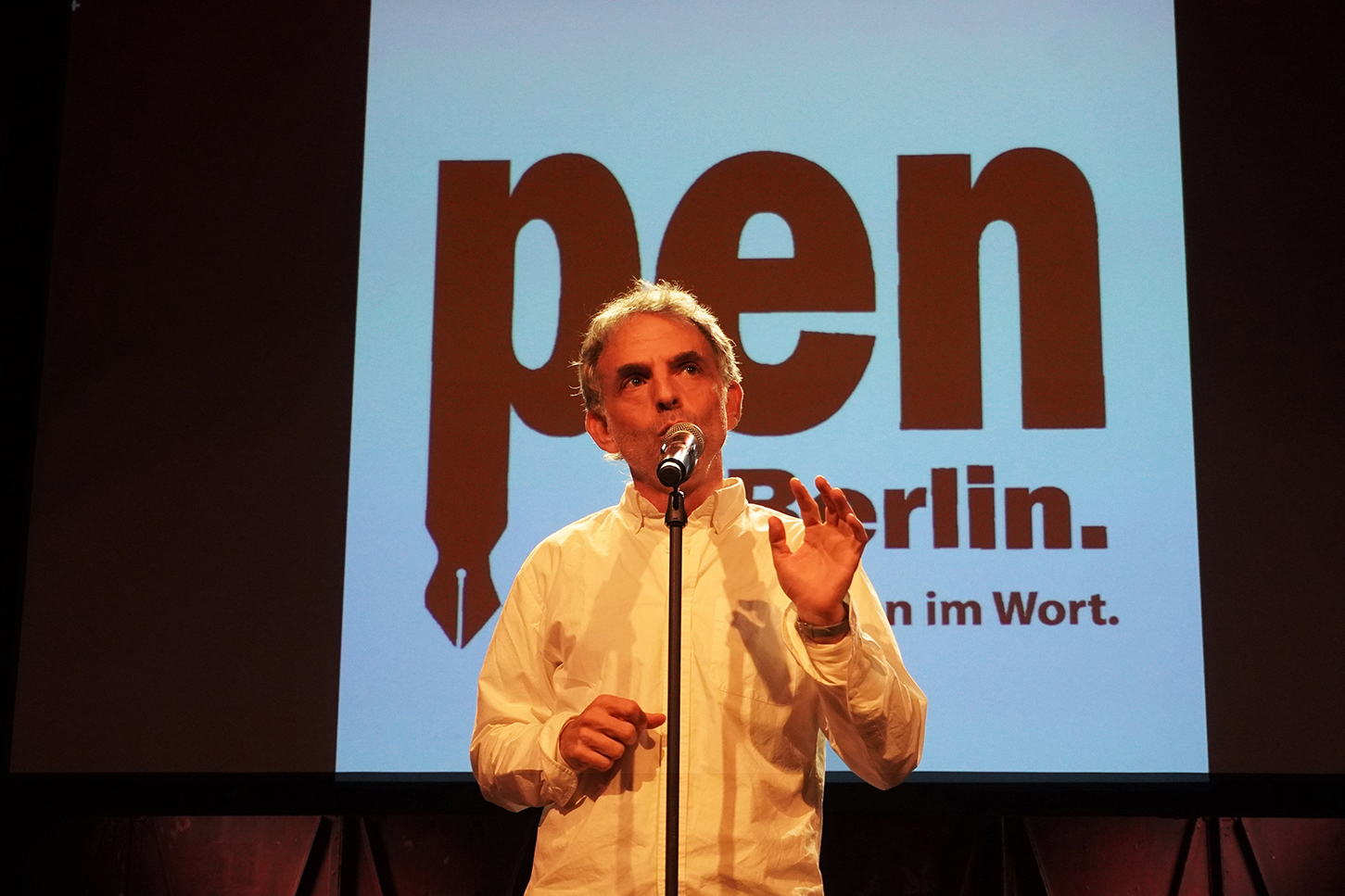

Opening speech at the PEN Berlin Congress »On we go«

2 November 2024, Fabrik Altona, Hamburg

(Also Eva Menasse’s farewell address as spokesperson of PEN Berlin)

Only this way – on we go

By Eva Menasse

[Listen to the speech (German)]

The morning before yesterday, Deniz Yücel and I – still the joint spokespeople of PEN Berlin, founded just two and a half years ago – received a press inquiry. We were asked to comment on the huge boycott call that had just gone public in the Anglo-American world. Close to a thousand writers and other cultural workers there are demanding that no one should collaborate any longer with Israeli cultural institutions and artists »who are complicit in violating the rights of Palestinians«.

As those responsible for PEN Berlin, we had to respond – as always, in coordination with my colleague, I therefore stated: »We reject cultural boycotts – in every form and in every direction. We are very much looking forward to this year’s keynote speaker, the Israeli writer Etgar Keret. And let me remind you that last year we also clearly opposed demands to disinvite our keynote speaker A. L. Kennedy.«

As an association dedicated to freedom of speech and of the arts, you can’t avoid such statements – even though, in my despair at the state of the world, I would rather have pulled the covers over my head again. I’m not responsible for the headline »PEN Berlin is outraged«; I merely sent an email. Strictly speaking, the colleague who asked couldn’t know whether I was outraged or perfectly calm. But that’s the media game – to drive clicks, colleagues add outrage to a clear statement.

This new boycott call – aimed, blindly and vaguely, at Israeli cultural institutions – does, however, give me the opportunity, at the end of my term as spokesperson of this wonderful new association, to set down once more a few principles I believe in with all my strength.

Cultural boycotts are always wrong

This includes the conviction that cultural boycotts are always wrong – at any time, in any direction, for any reason. Not least, the founding of the first PEN Club in London in 1920 – more than a hundred years ago – goes back to exactly this conviction: it was meant as a new beginning after the journalistic hostilities that preceded the First World War, in which many writers from the warring countries played a major part by allowing themselves to be enlisted in nationalist drum-beating. If we want to uphold PEN’s original principles, we must understand – down to the last ramification – what is at stake when artists are boycotted.

We do not know what our esteemed colleague Etgar Keret will say tonight – just as we did not know, last year, only a few weeks after October 7, what the equally esteemed colleague A. L. Kennedy would talk about. We had invited her three quarters of a year earlier, as the famous writer she is, by no means as an expert on the Middle East. Later she was criticised for having signed BDS petitions in previous years. But if one is fundamentally opposed to cultural boycotts, then one cannot boycott people who once signed in favour of a cultural boycott – simply because every human being, and every writer too, is so much more than two signatures – as in Kennedy’s case – and so much more than their citizenship – as in Keret’s case, for example.

When, shortly after last year’s congress, we began reaching out to Etgar, we already suspected that, a year later, this too might turn into a scandal – for exactly the opposite reason, though not necessarily in Germany.

Yet precisely that – scandals arising from diametrically opposed reasons – offers a fine opportunity for insight. Just as little as one can hold Etgar Keret, a decided critic of his own government, responsible for what the most right-wing government Israel has ever had is presently inflicting – both deadly and moral devastation in the region – just as little should Adania Shibli, the award-winning Palestinian author, have been casually and unthinkingly associated with the atrocious Hamas terror last year, when a prize ceremony at the Frankfurt Book Fair was declared »inappropriate at that particular time«.

What a presumption that was! What a disgraceful failure on the part of German newspapers – and of writer colleagues as well – who allowed themselves to link Shibli and her great novel »A Minor Detail« to eliminatory antisemitism already in the headlines! And why, this year, has no one even asked what became of that postponed award ceremony?

And let me add another example – for only when we consider them all together do they reveal the meaning I am trying to convey. Two years ago, I opened our first congress with these words: »It is inappropriate to keep demanding of Ukrainian writers that they at least acknowledge the literary worth of Pushkin or Dostoevsky – just as inappropriate as to expect every Russian artist first to take a ritual anti-Putin oath. (…) Yet precisely for that reason, in times of war, the conversations that can only be held outside the war zone are a precious good. Making sure that they continue must remain our goal.«

That holds true even more today – for every conflict zone in the world. Conversation and debate here are something fundamentally different from there, where people kill and die every day. Only fanatics fail to grasp that distinction.

At the Frankfurt Book Fair, which ended two weeks ago, we – PEN Berlin – hosted a major focus on Italy. We collaborated with those Italian writers who had publicly opposed the official guest-country presentation of the right-wing Meloni government. Not only had official Italy failed to include its most famous author, the anti-Mafia writer and outspoken government critic Roberto Saviano, in the delegation, it also avoided precisely those discussions that our Italian colleagues were burning to have – discussions about the rightward drift across Europe, about the defamation of authors, about manipulation and intimidation within the cultural sphere.

We were proud to have on our PEN Berlin panels the most renowned contemporary authors of Italy: Saviano himself, but also Paolo Giordano, Nicola Lagioia, Donatella Di Pietrantonio, Francesca Melandri, and Antonio Scurati. They spoke with extraordinary force about what it feels like to suddenly find yourself singled out and attacked across the media landscape. About how it feels when your colleagues distance themselves, saying things like: well, perhaps he or she didn’t really need to use such harsh words. Maybe they did go too far. Why do they have to get involved in these things at all?

And that, in turn, brought to mind Salman Rushdie’s powerful autobiography »Joseph Anton«, written during the years he spent in hiding under the fatwa against him. He, too, describes how painful it is when your fellow writers withdraw their solidarity – almost more threatening than the fact that fanatical murderers are out there looking for you.

The fear of authoritarian rulers

At the book fair, our Italian colleagues and we often spoke about why it is so often writers against whom authoritarian regimes – or those democracies that have begun to slide rightward – strike first. I know this from my own country, Austria. As early as the year 2000, the far-right Freedom Party, then part of the government, launched a vicious public campaign against writers like Elfriede Jelinek and Peter Turrini.

And in Turkey, once again, a trial is under way against the award-winning writer Yavuz Ekinci, who is also associated with our organisation – a trial based on a novel. A novel that could send a man to prison.

Why the writers, then? What makes them – who so often feel powerless themselves – appear so dangerous in the eyes of those in power that they must be hunted down and silenced?

There are many answers to that question, and I won’t attempt to list them all here. But perhaps this much can be said: writers are individualists. They have chosen a path that is anything but easy, but that very independence is what makes them dangerous. Through their works of fiction they reach audiences that cut across political convictions.

Let us keep that in mind – the fear authoritarian rulers have of writers – when we, living here in safety and peace, begin to think that this or that person should perhaps not be given a stage, should perhaps not receive a prize just now. Let us remember that we, who so loudly lament the polarisation and narrowing of discourse everywhere, might also have our own share in it.

Two and a half years ago, together with Deniz Yücel and many others, I threw myself into this mad adventure of founding a new PEN – because it was what I had missed most in Germany: an active, vibrant association of writers.

A coming together of people who write – all of them individualists, often enough contrarians – yet who value their smallest common denominator, »We can write freely and without interference in this country«, highly enough to forge it into a strong platform.

A platform that defends freedom of expression, of the arts and of academia – for everyone and in all directions – and that, when necessary, organises controversial, difficult, and delicate debates itself. A platform broad and solid enough to help at least some of those colleagues who, in their own countries, are persecuted, imprisoned, tortured, or forced into exile for nothing more than what they wrote or said.

A platform for persecuted voices

»Whoever saves a single life, saves an entire world« – that is perhaps the best-known line from the Talmud. Because this association exists, the Turkish-Kurdish poet and novelist Meral Şimşek now lives safely in Germany, together with her grown sons; the Afghan journalist Nasir Nadeem; the Iranian LGBTQ activist Sareh and her two children; the Iranian-born poet Mahtab Yaghma and her six-year-old son; and the Moroccan journalist Imad Stitou.

We have been able to support other colleagues in more limited ways – helping them find housing, navigate the health insurance system, connect with publishers, or secure a temporary residence permit to allow them to breathe freely for a while, away from stress, trials, and threats.

Later this evening, you will hear brief presentations about three other colleagues who have been imprisoned for years elsewhere. These three are only a glimpse of a shockingly large number worldwide.

That, in any case, is our core task: to provide a platform and human rights work for persecuted writers. With PEN Berlin, we have built a structure that those we have brought here must be able to rely on.

When I look back today – almost exactly thirty-six months – I find it almost hard to grasp how much more we have managed to accomplish. We have presented programmes at five book fairs, organised three cultural congresses including this one, held around a hundred events – readings, debates, discussions – and issued dozens of press statements and public interventions.

Then, just this past summer, came Deniz Yücel’s masterstroke: the much-praised and widely covered 37-part series of public dialogues across eastern Germany, titled »You Can’t Say Anything These Days«, on freedom of expression and democracy, which toured Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg ahead of the regional elections.

We also managed – almost on the side – to navigate the not entirely obstacle-free path into the umbrella organisation PEN International, and did so in record time.

Our membership has grown from 370 to over 700 – which, logistically, is no small challenge. And the extensive media coverage of our work, which in those wild early days was by no means always friendly, confirms at least this much: we have become a cultural and political player of sorts.

As newcomers, we had to – we had to keep drawing attention to ourselves, at the risk of annoying some of our own members. But that was also part of the human rights work at our core – I’ll repeat that once more – because it was precisely this visibility that allowed us to get meetings with policymakers, to build networks and partnerships, to apply for funding, and to organise scholarships, residence permits, and housing for the colleagues I mentioned earlier.

That is the PEN Berlin I’m proud of – in all its breadth. Taken together, this is the work of the past two and a half years.

For a long time now – and, I’m afraid, in vain – I’ve been wishing the media would pay more attention to this side of our work when they so gleefully report on our conflicts and the occasional resignation. Where is the long feature on Meral Şimşek, tracing the upheaval of a life suddenly in exile? Where is the interview with Sareh, who once sat on death row under the mullahs, or with the poet Mahtab Yaghma, on the current situation in Iran? How is Imad Stitou, who spent months underground in Tunisia before, after enormous difficulty, we finally managed to bring him to Germany?

Happily, there are by now countless books about Jewish exiled writers of the Nazi era – yet still so few about the exiles of the present. They are two sides of the same story. Exile – especially for writers, who lose not only their home but also their language and their audience – is always a human catastrophe.

Together with Deniz Yücel – to whom I want to offer my heartfelt thanks here for the near-insane effort of the past two and a half years, for his inexhaustible energy, creativity, and humour, and also for the nerve-wracking debates that, in the end, always pushed both of us – and the association itself – forward – together with Deniz, then, I fully agree on where the true and measurable effectiveness of a venture like PEN Berlin lies: in this human rights work.

And not, in the larger picture, in this or that press release, or in the one that never came out; not in a clumsy phrase in an interview, or in the outrageous remark of some member.

We will not solve the conflict in the Middle East, nor the war in Ukraine, from here and by resolution. And it borders on the absurd, in my personal view, when PEN centres issue resolutions condemning the resolutions of other PEN centres. None of that changes the course of the world – but it distracts everyone from the real work.

What makes us strong and credible

What we can and must do is pull ourselves together anew every day – to keep working together, here in this association, for instance. Every day, we must examine and overcome our reservations about others. We must keep choosing personal, face-to-face conversation over the lazy thumbs of the internet – the thoughtless clicks that fuel heated campaigns against people or institutions whose alleged failings we might never have noticed ourselves.

What makes us, as PEN Berlin, strong and credible is our diversity – our breadth of outlook – for as long as we can preserve it. If we lose it, we’ll become something like a lobbying group – and even those, these days, are riven by division.

One of our guests at this PEN Berlin Cultural Congress, the world-renowned Irish writer and essayist Fintan O’Toole, analyses – using the example of the bloody Irish conflict – the unhealthy but emotionally comforting rewards that division and polarisation offer to those who give themselves over to them. They attract people who, like probably all of us, are often overwhelmed and frightened by the state of the world – and therefore surrender to that false intimacy produced by the banal binary of us and them.

As Fintan says, when that happens, you no longer look too closely at who those people beside you actually are – the ones shouting in unison, the ones you might even be ready to march into battle with. The main thing is to define the supposed enemy – and to be sure that you yourself are nothing like them. It is the negative identity of opposition.

Perhaps the hardest thing today, therefore, is to stand against your own side – to keep questioning the convictions of your »own people«, to notice when they harden into dogma. In the past, it was often artists and writers who stubbornly resisted when everyone else was swept along in a single direction.

I believe that, in the end – for all the bewildering complexity of today’s world – it is not so difficult: we have to stand with those who work against division, who strengthen the platforms of dialogue, who search for the smallest common denominator and make sure that conversation does not fall silent.

Only that way – only by doing so – will we move forward.

In this spirit, I wish us all an inspiring, instructive and, hopefully, also an entertaining congress – and to »my« PEN Berlin a brilliant future, one that will be measured, above all, by the constructiveness of its controversies.

* Eva Menasse, born in 1970, is a novelist (»Vienna«, »Dunkelblum«) and essayist (»Alles und nichts sagen«). From June 2022 to November 2024 she served as spokesperson of PEN Berlin.