Keynote by A.L. Kennedy at the PEN Berlin Congress, 16 December 2023

I’m sorry everything is shit

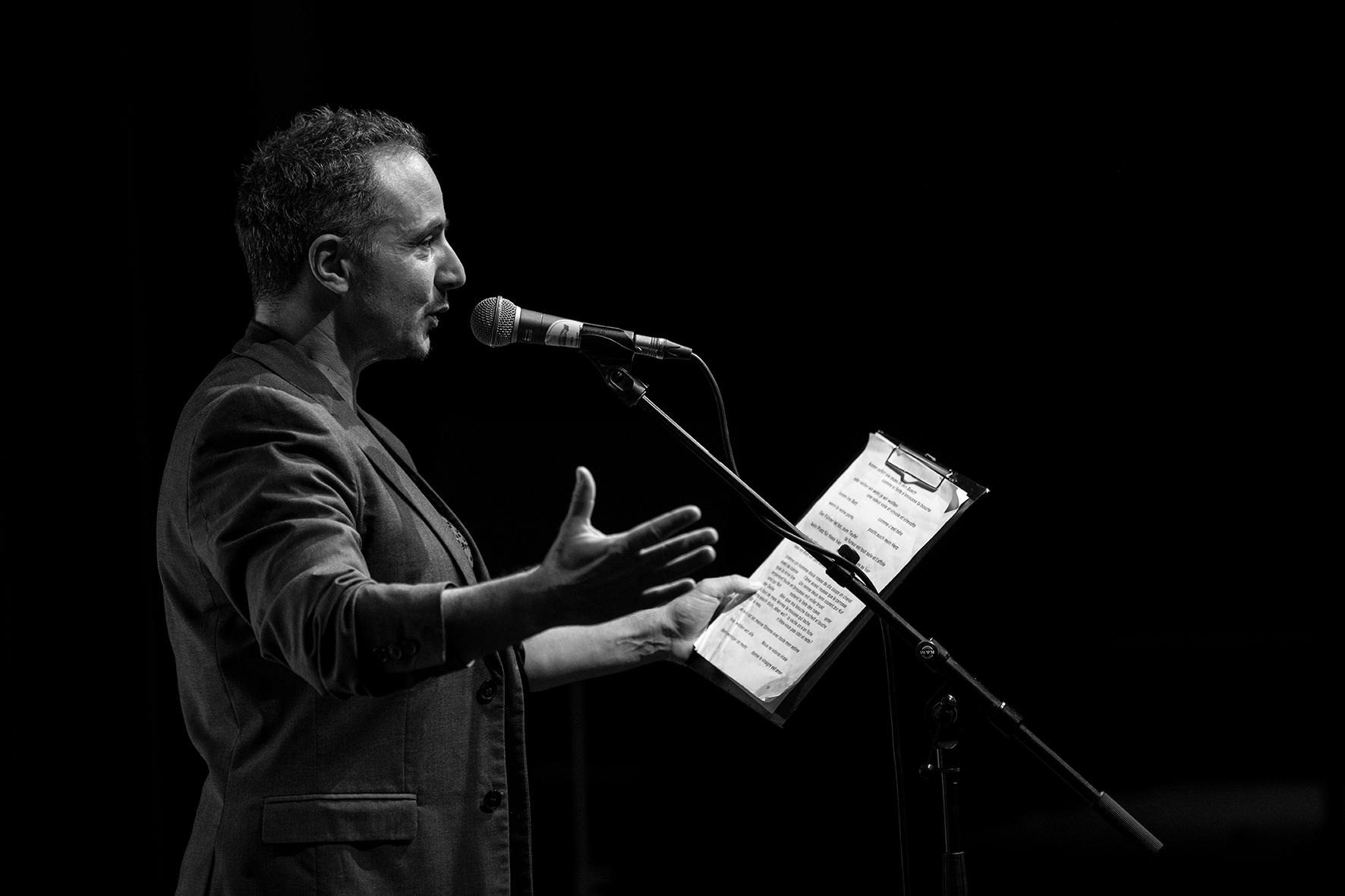

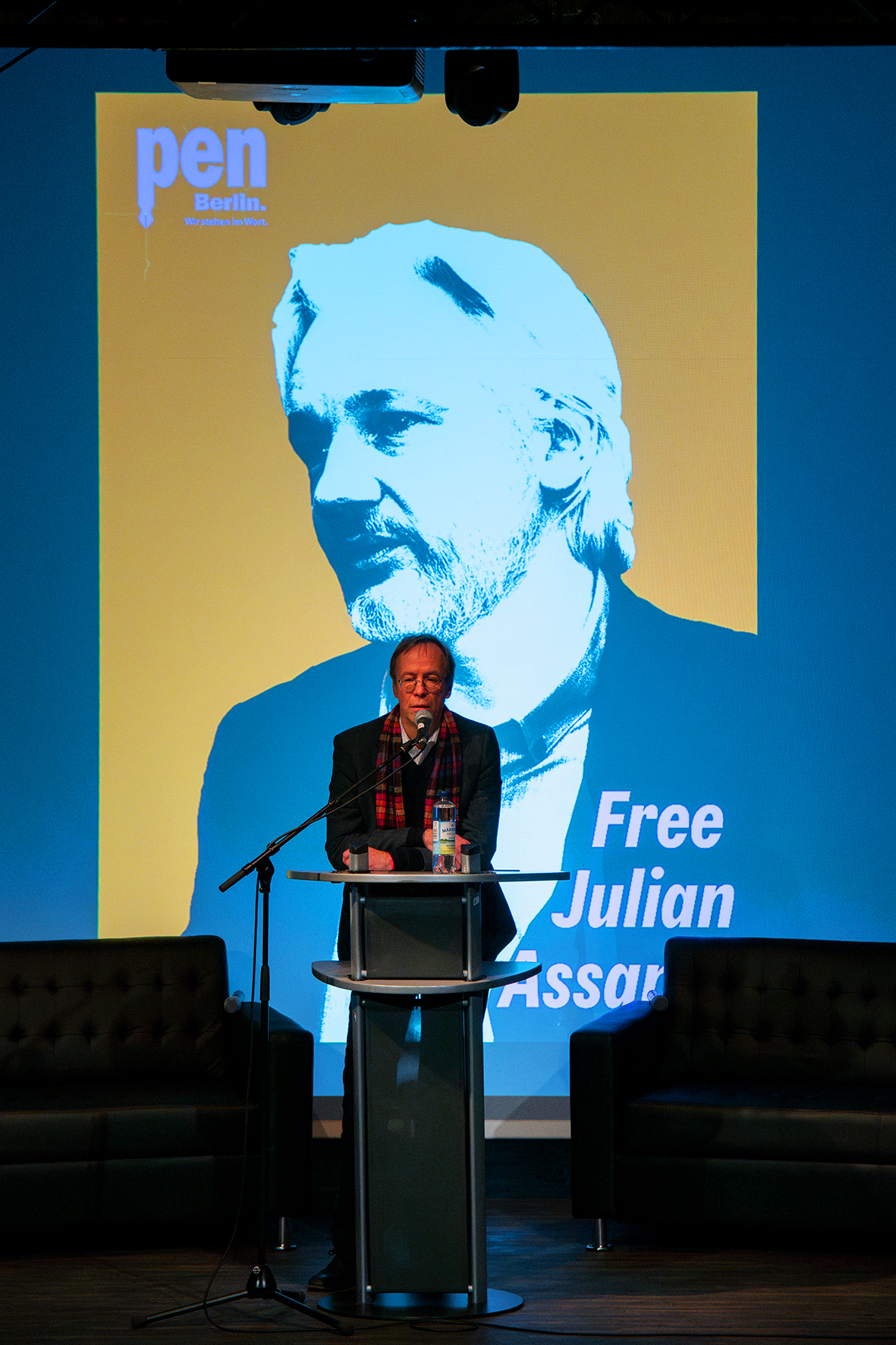

The writer A. L. Kennedy gave the keynote speech at the PEN Berlin congress »Mit dem Kopf durch die Wände« on 16 December 2023 in the Festsaal Kreuzberg in Berlin. But only in digital form because, as we announced in our press release, she was stranded in London.

This is the third speech of my autumn and – because you’re PEN, an organisation which defends writers, I’d like to talk personally about writing: about why writing, why writers, why do we do what we do? Why do we have – sometimes – the privilege of more audible speech? Why do the opponents of democracy and humanity seek so often to destroy us?

I’m not saying that I or my work are examples of excellence – I’m just talking about writers and writing. Why defend them? We can be eloquent, but simple eloquence – is that precious? It can, after all, do harm…

So – an example – the UK government’s handling of Covid was the usual kind of disaster, our leaders behaving like an occupying power, encouraging us to discard each other. At that key time, our public discourse left us alone with often justified fears, anger and despair. As a result, roughly two thirds of Brits now do not believe our government works for us. This damages our democracy still further. Faith in democracy always fragments whenever the power voters lend to politicians is abused, Criticism of specific failures blurs into criticism of democracy itself. The more abusers of the public trust appropriate government – and low turn outs from disenchanted voters favour them further – the more governments become spaces where only abusers feel welcome. Society destabilises, human potential is wasted, the public discourse is corrupted enough to make the meaning of chaos, waste and pain begin to decompose.

But I know, from 30 years of experience, that writers working with truth, honour and professional craft stand in the face of inequality, distorted joy, suppressed creativity and stolen lives. Even in fiction – we work hard to bring characters impossibly close. Even virtual proximity promotes empathy and connection, even in a time of imposed distance.

I learned what a prison smells like

I began as a writer, working with people others often despise, insult, neglect and ignore – the disabled, the poor, the physically sick, the psychiatrically sick, the dying, the young, the old, addicts, prisoners, delinquents – ‘useless eaters, unlucky, outside people, kept from comfort. But I learned. They were all people. Every day, in buildings where staff did their best but nothing quite worked and buildings where even the staff did not quite work – I learned. All people are people.

I travelled between venues for hours and miles every day. I was always tired. But I learned being tired is not the worst thing one can feel. I learned my version of having no money was a step up for most of my clients, my new writers. I learned what a prison smells like.

And I was learning how to write, learning fiction doesn’t work unless I love the people I’m making, I don’t need to like them, but love is essential. And if I don’t love the reader – that stranger for whom I’m working such long hours – then I won’t work well enough to delight and sing in them. Love helped.

Exhausted, regularly ill, I learned that the only way to deal with the chaos of chaotic care and chaotic conditions and people in chaotic lives, chaotic bodies and minds, was to do the next loving thing. Everything might be flexible, but not love. These people, these writers, who might seem and sounded very different from me, who sometimes couldn’t write, or read, or speak – they still had voices. It was my job to assist them on to paper. There, they gained the status, power and attention we writers take for granted. Their writing brought them closer to their readers. Some readers were appalled by the proximity, guilty, disturbed – that surprised me – some were delighted.

Writers are strange people

So I helped people use words to reach others, while learning how to do that myself and I never forgot what intimate power that has. I never forgot that all people are people, all people have voices, all people have narratives. And in the blur and grind only aiming towards love got me through – that and the joy. There is nothing more joyful that someone finally trusting and discovering who they are and what they want to say, who they want to be. I was in my early twenties – seeing death, injustice, needless worry and indignity – but also such joy.

Writers are strange people, eccentric, self-indulgent (I’m not a pleasant person) but we are part of this loving, joyful process, this reminder us of our communal humanity. If we serve the demands of that process we will be delighted and authoritarians will hate us. We will work in the roots of democracy every day, feeding them, one small word at a time.

Organisations like PEN have always challenged authoritarianism, undemocratic regimes, oppression of individual writers’ voices, suppression of speech. Sometimes we maybe forget that the essence of writing is a friend of democracy, too.

When PEN was founded in the UK of 1921, authoritarianism was rising as it is today. An emboldened British ruling class was, as it is today, disproportionately powerful and beguiled by the idea that good fortune is predetermined by blood and soil, that privilege isn’t privilege but divine right. A group of prominent writers took steps to defend writers of fiction, professional liars, if you will. I think, because of the truths central to what we do: all people are people, all have voices, the world is a difficult place and needs mercy, a good life finds its way in pursuing the next loving thing. That sounds weak, unfamiliar, odd even as I say it – but love is the strongest thing. It is to Britain’s eternal shame that, were PEN being founded today, it would be controversial in an energy-sapping way, condemned as an alien contaminant, an example of a self-aggrandising elite.

But our words can be the sustaining secret in hell, the invisible hope that torture cannot always find. In fiction, we build convincing characters, designed to accommodate the reader, as no real person is. In so doing we build intimate, effective empathy machines. One heart at a time, we can be a part of change – it is our difficult responsibility to ensure we bend that change towards love.

We live in a dark time of mutilated children and burned hopes

In a world of battling narratives, intentional confusion, spin and reframing and psycho-engineered, targeted talking points, we write on. Effectively operational fiction says all kinds of things, but also implies – people are people, humans are human, we have many differences, but also wonderful, terrifying, frail and powerful similarities. And mind to mind, we say – Here I am. You’re not alone. I knew you might need this beauty, made for you in hope.

We live in a dark time of mutilated children and burned hopes, of power without mercy or even sense, impunity for the wicked and punishment for the guiltless. But if we despair, we surrender one of the few battle grounds where even the weakest can win: the imaginative space where individuals and whole communities can plan better futures. In an age of climate change, surrendering that space and that imaginative energy will be species ending.

But there are new challenges we must also recognise and overcome. Otherwise the structures disseminating information, delivering creativity from human to human will become hostile to human intervention, creativity, even human existence in ways that threaten us as all. Machinery created by an intersection of AI and endstage capitalism will simply make the ways that one soul speaks to another irrelevant and then redundant.

This push against imaginative expertise, narrative coherence and empathy is not unique to Britain. Feral new media have been able to corrupt, degrade and supplant the legacy media globally. Democratic institutions, corporations and individuals are affected by malign psychological influence globally with only a tiny global democratic response this far.

Does free speak support a democratic variety of voices – or the right to lie?

Many of us now have shiny accelerators of stochastic terror in our homes, our bedrooms, our pockets. We are not safe anywhere the internet can reach us. Organisations advocating for freedom of speech are no longer just battling thuggish suppression techniques, but bespoke narratives designed to penetrate. If freedom of speech is to survive, we have to define what it means – as we did after WW2. Does free speak support a democratic variety of voices, rights to be expressed – or the right to lie, slander and libel without limit, or consequence?

Algorithmic amplification of misinformation, disinformation and propaganda is now horrifyingly effective. As Mark Twain put it, the difference between a cat and a lie is that a cat only has nine lives. We all how well cats do online. From the Talmud, to Greek mythology, across the history of human civilisation we have acknowledged that malign speech is dangerous and have taken steps against it. But in the 21stcentury we have allowed malignance to proliferate. This wounds and kills people who are people every day.

Organisations like PEN need to be here to help create a context within which human values thrive. Quality writing, fully-formed narratives, familiarise us with completed thought, with lies that are declared as lies and truths that are declared as truths, with the complexity and danger and sublimity of our species. We need, as writers, to give nuance and sanity to the ideas of freedom and speech – just as much law on free speech contains nuance and rationality. Still, laws can be used to silence legitimate speech and, the more people you slander, the more perversely difficult it is for the law to name a plaintiff.

PEN needs to defend writers and human narratives from technology in another way. AI is a real threat, largely unaddressed. The mass-produced, micro-managed plagiarism engines like Chat-GPT and the rest threaten the ability of writers to work at all. Machine learning, free from any benevolent restraint, trained on the appropriated fruits of artists’ and writers’ labour, now stalks every area of human creativity, harvesting, mincing and reconfiguring. Educated by racist talking points, cultural stereotypes, the sexist assumptions of pornography and an attention economy which prioritises the manufacture of stress, outrage, anger and fear, AI is a problem for humanity as a whole. It could make writers extinct. The recent victory for the American Writers Guild is only the first episode in what will be a vast, desperate struggle. PEN must combat overt suppression by human actors, but it must also confront disinterested, amoral mechanisms, the operation of which will overwhelm and supplant writing for humans by humans.

And there will always be talking points along the lines of When so many are in pain and our planet is already both burning and drowning with worse to come – why talk about saving poems or poets and not the baby who needs food?

I’m not telling you to ignore the baby. Feed the baby. Of course feed the baby. I’m telling you sometimes the poem is why you know you have to feed the baby – every baby. More – if you don’t save everyone, then in many ways that really matter, you do not save anyone, not even yourself. In living and working as writers, building personlike people, making complexity comprehensible – we learn this. We live and work in a way that suggests why everyone is worth saving.

While human rights law establishes principles, we are among those who offer examples of why we defend and save humanity’ rights. When journalism wants to evoke empathy it borrows our techniques – runs long-form investigations of disaster victims’ lives, detailed accounts of community members and personalities, it offers narratives that reveal humans as human. That’s part of a psychologically and emotionally healthy public discourse. The more humane, quality narratives we have in every form, the safer we all are.

Compassion is not a competition

Many forces, ideological and commercial want us to live in environments of scarcity, of limited resources for which we compete. Many of the resources which make us most human – empathy, altruism, invention, hope – simply aren’t like minerals, or washing machines, or anything else you can sell.

If I am more happy you don’t have to be less happy. If we’re both happy, there’s a good chance other people start being happy, too. A public discourse where we are trained to believe there is only enough empathy for one crisis at a time, only enough help for one fraction of the world’s need, that everyone must compete for mercy – this leaves us all losers and ignores the ways we thrive.

It plays into the culture of fake balance and whataboutism, beloved of authoritarian talking points and lazy media. You feel empathy for these people? Then you must hate those people.

No. I can have more empathy. Compassion is not a competition – it is a beneficial contagion. Even if our media love horse races and binary options, almost nothing – apart from literal horse races – works like that. In a time when some journalists are dying to bring us the truth, I have no time for those others who look at difficult, complex narratives and decide to simplify, omit truths, favour power, ration attention. If something’s hard to understand, it’s our job to explain it better. We don’t blame the reader.

As writers, we create. That’s about the abundance of the world, making something from nothing, and explaining humanity to itself. To compromise, to do anything less, is unloving and lacks ambition in our culture, ourselves and humanity. A sick culture, hateful, compromised culture – we have always been at war with Eurasia, no, we have always been at war with Eastasia – sickens us.

In a culture where there are many voices, many moving and effective depictions of humanity and our reality then irrational voices, hateful voices are weakened. Why would dictators lock up writers – us silly little writers with our imaginary friends? Because tyranny relies on narratives to highjack our belief, uses our negativity bias to keep us isolated, outraged, uncertain and fearful of scarcities. If we pursue excellence, creativity, the callings of love, then we create abundance, coherence, self-propagating joys: a sense of life, even when we talk about sadness.

There’s an UK charity, Arts Emergency, that I love and support. Arts Emergency was founded following one of its own principles ‘Sometimes if something doesn’t exist you just have to make it yourself.’ They provide an alternative old boys network so the ‘wrong kind’ of people can still make art, give us what only they can. AE is philosophically, emotionally, practically, lovingly and abundantly effective. As another principle of AE says, Be Generous. Now Be More Generous.

And this isn’t theory. I have decades of experience of this off the page and I’m sure many of you do too. As writers we are interested in new writing, we can’t help it, so we work with new writers, writers who might need extra help, writers who need the help words provide. On the page, we make things out of nothing and they gain types of reality and nudge the world. This has changed my life. I am no longer shy, inarticulate, unemployable, frustrated, furious, alone.

Writing creates what we need until it exists in the world

I have seen writing change others for good. Writing makes what we need until it exists in the world. We might be broke and tired, but we live in abundance. We discover that a family memoire only ten people will read and a raw novel which becomes a bestseller and a group poem by unhappy social workers and a short story by a lonely child – they are all abundance out of nothing, all effect positive change just by existing.

They all show something of the secret which is who we fully and deeply are, something of the irreplaceable truth each one of us holds.

In the Covid time – that mass trauma for our species – how did we sustain ourselves? We reached for beauty, nature, love, rainbows chalked on pavements, theatre online, balcony singing, living room ballet, orchestras playing together while apart. And words were touch without touching. They always are.

The phone calls, online calls, condolences on what used to be Twitter, the poems and stories of griefs, of joys, fictions that kept us company – they were not a dispensable luxury, a childish indulgence. Words were clearly what they always are – a preservation and a propagation of life.

In lockdown, I wrote a novel, partly about lockdown. I also commissioned a friend to sew a pillow full of lavender: edged with lace, embroidered with flowers and also the words I chose – I’M SORRY EVERYTHING IS SHIT.

It was for my mother, to make her laugh in a time with little laughter and to tell her I understood. She hung it in the background during online chats, apparently a sweet old lady kind of ornament. But she knew what it said. At a time when our media were largely in lockstep, ardently respecting people who were clearly terrifying clowns, many of us knew EVERYTHING IS SHIT. There was a power and relief in saying this. Had loud voices, important voices, media voices said it enough, lives would have been saved.

Sometimes, writers make a phrase or a poem which keeps us company, deepens experience. Sometimes we just offer consolation – ‘I’m sorry everything is shit.’ That’s the beginning of a conversation which may end in change and that matters in a gaslit nation.

Writers and writing can have the power of promises, spells, prayers, prophesies. They can insist on fulfilment. This is both wonderful and dangerous. I would suggest that PEN needs to be about trying to preserve a robust, organic culture of abundance and humanity, of creativity and fully-formed, full-throated fiction, not just repeatedly-screamed shoddy lies.

Humans who seek to harm and dominate other humans want mediocrity and repetition. They have no interest in art which aspires towards remarkable humanity, or creates illusions of complex psychology, human truth, evocations of personality into which we enter, with which we can empathise. They want conjurings of poorly sketched subhuman threats. Those who wish us to have less power, less of everything, aim to keep us swinging between helpless anger and despair, in a place of inarticulate pain.

The powerful are petty and witless

Recently I was reading Joseph Darnand’s declaration on the founding of the Milice française in 1943. The Milice would become a force notorious for torture, summary execution and the consignment of Jewish human beings to the vile machinery of the Holocaust. Darnan describes his militia as necessary to enliven public life with its vigilance, its propaganda and its action to maintain order within the state – already a bizarre and unwieldy cocktail of disparate elements.

Only repetition of such nonsense in a supportive atmosphere of Gleichschaltung and threat would render it credible. He goes on ‘A l’heure où chacun s’interroge et doute, il faut créer une MILICE pour le maintien de la France…’ At a time when everyone questions themselves and doubts, it is necessary to create a MILICE for the maintenance of France.

Authoritarianism, dehumanisation, always works this way – You question and you doubt – because we made you, because our fracturing of any agreed reality was necessary to permit our monstrous wrongs which will, in turn, fracture and what being here and being you could even mean.

When we talk now about a rise of fascism and a troubling lack of enthusiasm for democracy – slow, flawed, dull democracy – this is framed as bewildering, unstoppable, imbued with the power of strong men doing strong things. But it’s an inevitable result of cultures allowed to shrink, warp, deny reality, impose scarcity and cultivate misery. We – myself included – have created a time when more and more people question and doubt. Maybe we were distracted, morally compromised, maybe scared – it doesn’t matter why – we didn’t do all we could to preserve a healthy culture. We failed to serve the obligations of love. And, meanwhile, our media told us – NOTHING IS SHIT. And that was a lie.

It was a lie over 30 years ago, when I was working with writers who first told me about Aktion T4, the Nazis’ attempt to destroy Germany’s people with disabilities – a rehearsal for further destruction. Some of my clients already expected something very like 21st Century Britain, a country repeatedly condemned by the UN for the abusive treatment of our most vulnerable. Our excess death total rises, while new groups are marked for hate. And every person lost is a world gone beyond recalling. Every one.

We live in a time of horrors. The powerful are petty and witless, the anger of the young is groomed and harnessed. The rage arising from propaganda, injustice, scarcity and indifference is being gathered and directed. What would a sonnet or a novel do about that? Why shouldn’t we question and doubt and despair – wouldn’t that be natural. In times of confusion, doing the next loving thing gives us clarity. When so many have so many more pressing reasons for despair, shouldn’t we just work and look for joy, those of us who are still free to?

Writers and writing change people in detail, can make them strong, happy and more fully, more expressively and abundantly themselves. Our personalities are, in part, a story made of words. We can gain authority over our narrative and cease to be vulnerable, infantilised, alone in the dark while some scary authoritarian daddy tells us fairytales of problems only he can fix.

Old and new conflicts rage in our minds

I’ll end with a story. I was recently in a writers’ centre in the Highlands of Scotland – working with new writers. As ever.

Northern Irish writer Bernard MacLaverty came and read to us from a story set during the long years of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland – a conflict which once seemed eternal, but which is slowly healing now. The piece showed a family coming home from a happy trip. They witness paramilitary thugs begin beating a man in the head with a hammer and laughing.

This is all described clearly, is quiet enough to horrify, detailed enough to be real. The family rescue the man. They leave him, bleeding and perhaps dying, at a hospital. Later the rescued man writes a public thanks to his unknown saviours. And they are happy to know he’s alive. They are grateful he told the story – they think that was kind.

We listened, at peace, although new and old conflicts were raging within thought, if not sight. Bernard finished and said of one new conflagration, ‘…we had a situation like that in miniature, but miniature doesn’t matter if someone has been killed…’ He said what any writer worth the name always says simply by writing. We live in a world and in an information space where Stalin’s cynicism could thrive – A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. Our world has so many millions of deaths, many not even statistics.

But functional writing creates pieces and cultures within which, one death at a time, the millions are mourned, the universal talks to the particular and there is some hope of preserving those who still live. To save an individual we have to think what we might lose if they were gone. To save our species – something which will involve vast global invention and struggle – we have to understand why we’re worth it.

In the midst of provocations and distractions, artificial competitions and fake scarcity, please PEN – do what writers do, master the narrative, navigate the complexity and the nuance and speak to us, for us. Defend those whose lives are devoted to speaking for us all. I’m not a good or a loving person, but I know what works – be guided by love. I’m sorry everything is shit. But we can change that.

This is the manuscript version of the keynote speech by by A. L. Kennedy on 16 December at the PEN Berlin Congress in the Festsaal Kreuzberg. Translated from the English by Ingo Herzke.

* Alison Louise Kennedy, born 1965, writer, comedian and associate professor in creative writing at the University of Warwick. Last book first published in German: »Als lebten wir in einem barmherzigen Land. Roman« (Hanser, 2023)