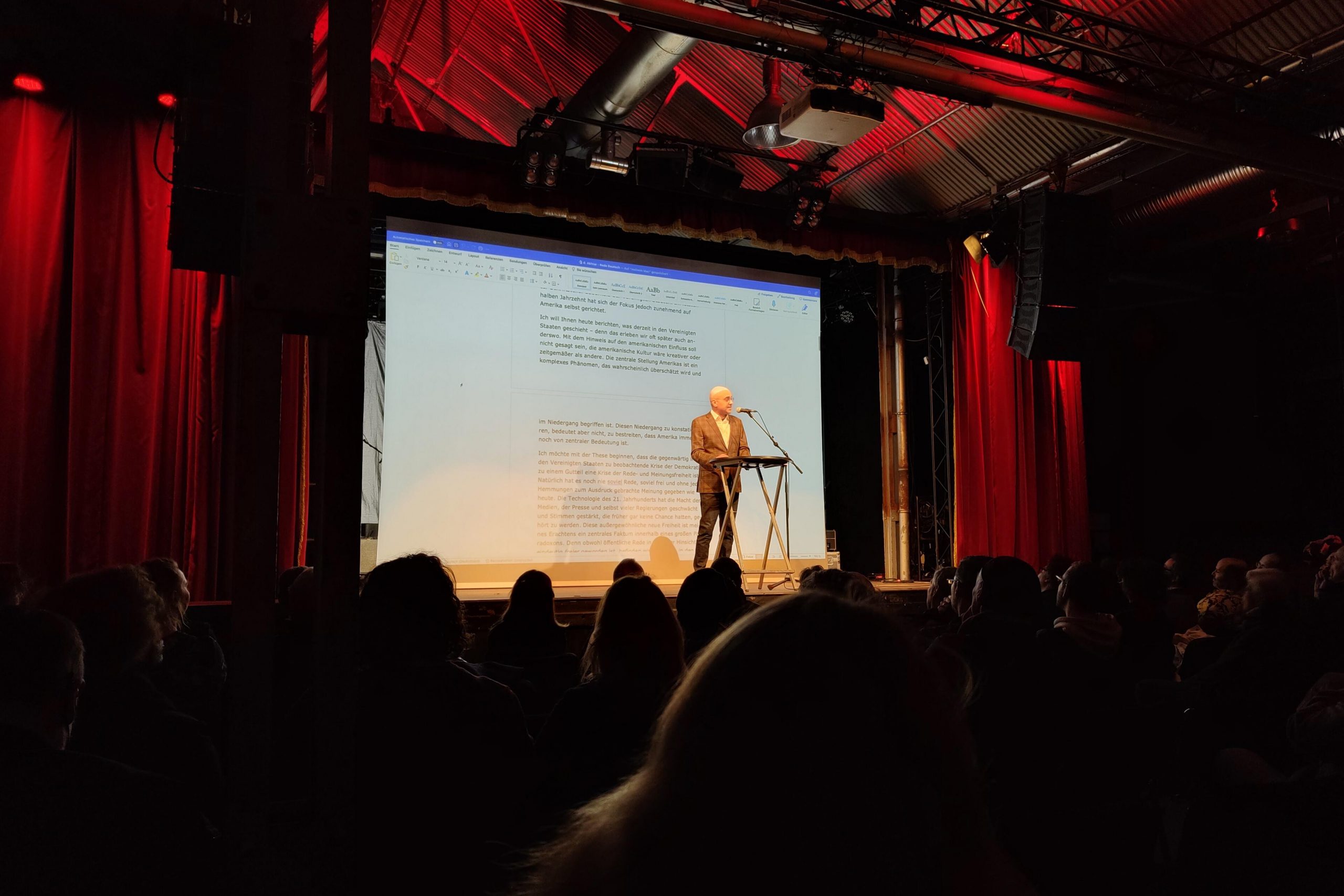

Speech for PEN Berlin’s first congress, December 2nd 2022

A climate of digital intimidation

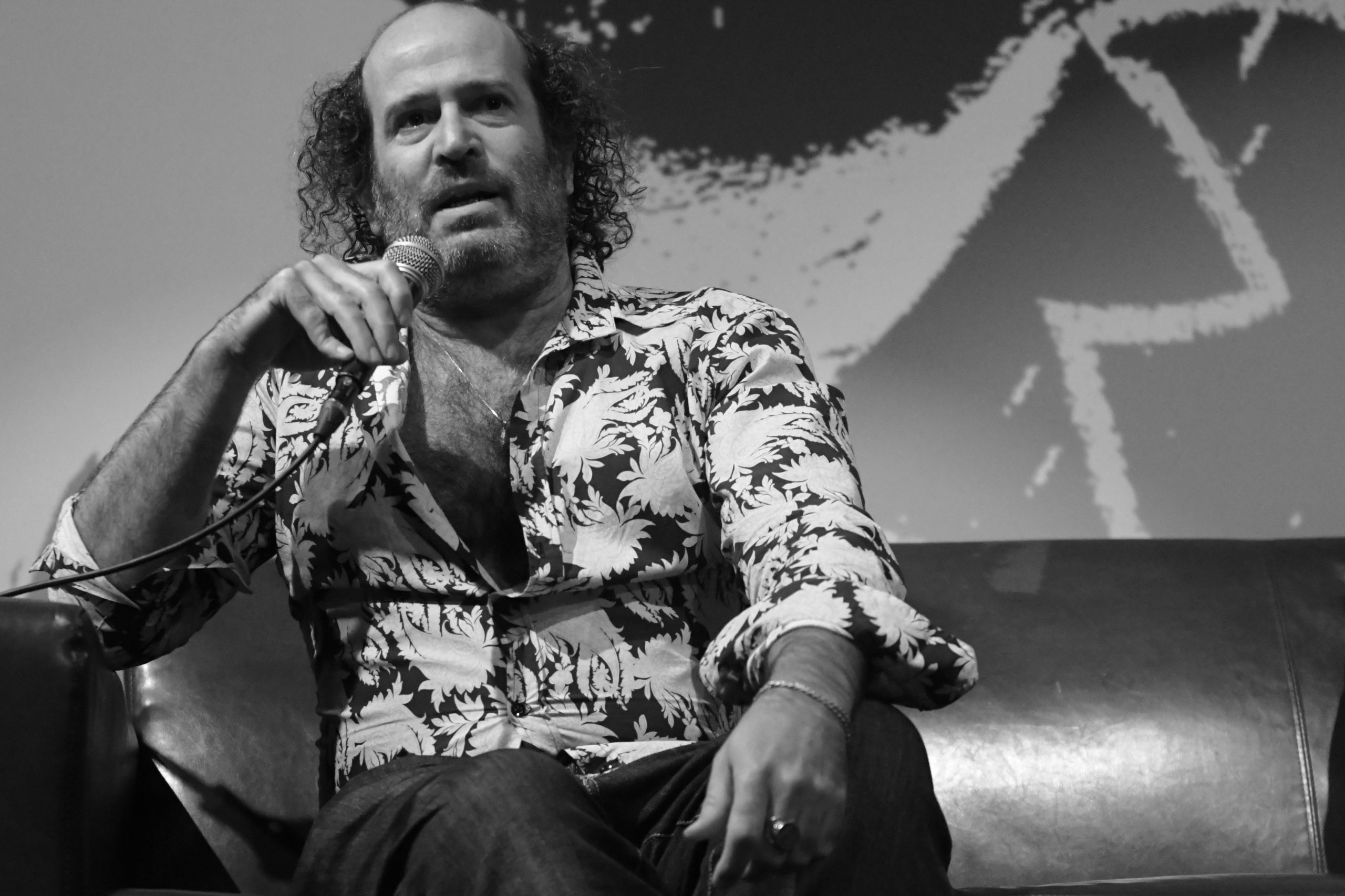

By Ayad Akhtar

Dear Colleagues,

it’s a great delight to be here in Berlin, on the occasion of your first congress as an organization. Thank you for the invitation to address you all. I’m deeply honored and hope what I have to say to you all today is in some way meaningful as you embark on your work together.

As many of you know, PEN was started 100 years ago in the aftermath of the first world war, in part as a way for writers to convene, contemplate together, and exercise a shared role in the world, beyond the role writers can play with their individual writings.

If writers, as individuals, operate as nodal points of conscience for their societies – how much more powerful could they be when gathered together, pooling their efforts, marshalling their collective influence in service of making the world a more just, a more truthful place.

For much of its history, PEN America, the chapter PEN where I am now president, spent the majority of its time focused on threats to free expression and to writers outside of America. But in the past half- decade, our chapter’s focus has become increasingly centered on America itself.

In considering what I might have to say to you today about our shared mission as members of PEN, it occurred to me, perhaps, that bringing news of what I am seeing take place in the United States would perhaps be of value – knowing that what happens in America can tend to start happening elsewhere over time. In pointing the vector of American influence, I don’t mean to make a case for American culture as somehow more creative or more attuned to the times. American centrality is a complex phenomenon – likely, overdetermined – and likely in decline. But to acknowledge this decline is not to deny the fact that nevertheless, America does still remain central.

Crisis of free speech

I’d like to start by suggesting that the ongoing crisis in democracy that we’re seeing in the United States is – in many ways – a crisis in what I might call free speech.

Of course, from one perspective there’s never been more speech, more speech freely spoken with fewer barriers than ever to being heard. Twenty-first century technology has de-centralized the power of the media, the press, and even many governments from preventing voices from being heard that might otherwise not have been heard. This extraordinary freedom, it seems to me, is the central fact at the heart of a great paradox.

For as speech has become clearly freer in one sense, we find ourselves in the midst of a cultural shift in the United States to a discursive environment rife with punitive interdiction, where today’s politics of identity imposes contradictory moral maps about what speech is acceptable to what group and what speech isn’t. A climate of digital intimidation is on the rise, and with it, a fear to speak and even to think freely. On the rise as well is a profound and widespread intolerance to points of view deemed unacceptable, or even »immoral«.

Complicating and contributing to this perplexing picture is the technology at the root of our new, unprecedented freedom to speak, and at the root of the increasingly toxic environment in which that freedom is being exercised. Social media platforms have honed their monetizing models and learned that it pays to encourage anger, volatility and dissension. Sophisticated metrics are brought to bear on user speech, posts, photos, likes and comments – and these metrics form the basis of a programming process that amplifies what is most outrageous and most divisive.

What I am describing is an algorithmic curation of the world’s speech, millisecond by millisecond, that makes money – a lot of it – by sowing conflict to create engagement, harvesting the data that results, and selling ads at every possible step along the way. This business model has reshaped not only what it means to speak in the public space, but maybe more importantly, what it means to listen.

Loss of meaning

For another effect of this monetized, technological sorting of human speech is the creation of a digital apartheid, where separation of groups takes place along lines of identity, groups increasingly open only to hearing only what reflects their vision of reality. Opinion, then, not truth. But opinion elevated to the condition of truth. And so it is that the ground is laid for the extraordinary proliferation of – and passion for – disinformation as a social prime mover.

One of the casualties our curiously immured era of free speech is meaning itself. For as an interest in truth recedes, supplanted by a preferred versions of reality that suit the story a given group prefers to hear; as interest in truth recedes, so does meaning in language along with it. Now words and phrases are markers of identity, signifying belonging, position in the hierarchy, or the color of your skin, and these symbolic significations determine the meaning of what you say far more than the words you use to say it.

Case in point – as I sit at my desk, writing this speech in New York at the end of November, there is much talk amongst a circle of editors and agents I know about a book proposal that has been submitted to all of the major publishing houses. The proposal is for the first full-length, scholarly biography of Medgar Evers – one of the most important figures in the American Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. The author of the book proposal in question is considered a leading specialist of Evers in the United States. But that proposal has not found a home, because no publisher is willing to take it on. Not now, not in this climate, because Medgar Evers was Black, and the author of the book is white.

I mention this anecdote not because it’s unique; it’s not. Not in today’s environment where scholars are routinely discouraged from taking an interest in subjects seen as not belonging to them, an environment where young writers are told they cannot write from points of view that are not their own, an environment where there is growing reluctance to express any sentiment or view that could be construed as harmful to some group or other. Among the most important thinkers in America today, Henry Louis Gates Jr, bemoaned the situation in a speech he gave to PEN America in 2021. I quote him here:

»The idea that you have to look like the subject to master the subject was a prejudice that our forebears – women seeking to write about men, Black people seeking to write about white writers – were forced to challenge. Toni Morrison’s master thesis at Cornell was a study of Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner, completed in 1955, the same year that Rosa Parks refused to move from the white section of that public bus. Any teacher, any student, any reader, any writer, sufficiently motivated and committed, must be able to engage with the subjects of their choice, freely and without pre-qualification. That is not only the essence of learning, ladies and gentlemen – that is the essence of being human.«

Narrowing of intellectual curiosity

Gates, a scholar at Harvard, was commenting on a trend prevalent not just in publishing, but in higher education at large. A narrowing of intellectual curiosity, a focus on race and identity as the sine qua non of authorial legitimacy, an intellectual tribalism that is selling »short the human imagination.« His eloquent defense of the freedom of the intellect was all the more convincing coming from him, an African-American, which was what so many in the room felt and said after the standing ovation. Many remarked that they hoped somebody might actually listen, because he was Black, and because no one was listening to any number of similar defenses when spoken by white authors.

Impartial, unprejudiced intellectual and creative curiosity is on the decline – a development defended fiercely by many who invoke the idea »appropriation« as the historical injustice in need of redress. Roughly put, »appropriation« accuses some groups of people as having forfeited their right to the cultural material of other groups of people. I’m sure you’ve heard news of silly, overblown episodes like the students of Oberlin College protesting the serving of sushi in their university cafeteria. But the logic of »appropriation« has far more serious ramifications, positing, as it does, that the act of speaking in the voice of someone different from yourself is problematic, for it is inherently riven with a threat of harm. Speaking in the voice of someone different than yourself. Isn’t this at the root of the magical act of empathic enlargement that defines literature? Increasingly the answer to that question is no.

For if you write about a group you don’t belong to, we’re told, you run the risk of shaping a representation offensive to members of that group, or worse, a representation that could encourage others to harm members of that group. Which is how, we are told, Picasso’s depictions of African women are responsible in part for the genocidal murder of them by Europeans. Such harms caused by speech in its various artistic and non-artistic forms are of paramount concern, and it is assumed that the dangers of appropriation far outweigh the benefits of empathy?

Unipolar formulation of power

It turns out there are some who actually appear to believe that. And so, a lot of what passes for cultural curation now revolves around policing incidents of appropriation, and theorizing the attendant outrage. We’ve seen this in exhibit after exhibit of visual art in America, from Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmet Till to the long delayed Philip Guston exhibit. And it is with us in literary circles and publishing houses, where sensitivity readers are hired to scour submitted manuscripts for potentially offensive representations, and in Hollywood, where networks and studios are spooked, and where writers’ rooms are increasingly a ground zero for battles about who can and cannot write characters with identities differing from their own.

The issue here is not simply one of aesthetic and narrative judiciousness. It’s not just a matter of whether the writer has the knowledge and good sense, the humility, to tell the story »well« – something which all of us in this room want to be sure we are able to do, whether we’re writers of fiction or non-fiction. No, the issue here is not just about being the kind of writer who gets it right. In fact, the issue is considerably more wide-ranging, and reveals a pernicious emergence of a way of conceiving of human creativity. Increasingly, creativity is being understood not in relation to the demands and possibilities of the human imagination, but rather, in service of an analysis of power.

The analysis of power to which I’m referring, developed in the social sciences, envisions power as the defining axis of all human knowledge. What power you hold, it suggests, defines what and how you know. So it is that Edward Said’s seminal study, Orientalism, could usher in an age of thoroughgoing suspicion of Western interest in the cultures of Islam and the Levant. Said’s masterwork was of a piece with its times, introducing a way of thinking about power in cultural production which challenged those in power, and seemed to posit that those who didn’t have power were somehow closer to the truth.

When this logic of power is mapped along contemporary axes of race and identity, a knee-jerk Manicheanism often follows: whites are suspect as holders of power; elevation of non-whites to positions of power is seen as a self-evident good. This is, of course, in part a simplification, but only in part – for what I’m describing is an aspect of the deep context of the atmosphere in the cultural sectors of America today.

But it turns out an analysis of power valorizing the victim of history is not only flawed, it’s also a game anyone can play. Whites, too, can find their grievances and complain about the harms of speech with as much vociferousness as the rest of us.

Much of what’s unhelpful about this view of things is its unipolar formulation of power itself. Finance, tech, the corporate order, national governments and the non-governmental sector, the fourth estate, institutions of higher learning – all are holders of power. But all are not equal offenders. And indeed, it is only with the participation of these centers of power that we can expect solutions to our larger dilemmas – climate change, artificial intelligence, rising political chaos.

In other words, hierarchy is not the enemy – and the process of influencing holders of power to act responsibly is less about revolution, than it is about speech, and fostering an environment of free speech where truth matters. More on this shortly.

A very hard time for truth

Some of the intellectual and cultural dysfunctions I’ve shared here today bear a family resemblance to things we’ve seen in the past, the result of what we sometimes call »ideology« – or doctrine passing for analysis.

As writers, we are familiar with – sensitive to – the obfuscations of ideology. Indeed, such obfuscations are often our target of choice. Pursuit of the truths buried beneath these layers of ideology makes up much of the history of the world’s best and most important writing. This commitment to revealing truth is, above all, what I believe unifies us here in this room today.

But as agents interested in truth, part of our dilemma is that our current era of free speech is a very hard time for truth. Some of it dates back to the intellectual de-centering of truth that the latter half of the last century brought us; but that isn’t the only reason truth no longer appears to operate upon us with the persuasive force that should seem to define it. Indeed, today, it isn’t just a manner of speaking to acknowledge one man’s truth is very much another’s lie; what is disinformation to some is gospel to others. The jockeying of competing truths in our information ecosystems increasingly define what is most broken in our free speech today. That our society could become so utterly beholden to the digitally curated diffusion of intentional untruths passing as their contrary is an astonishing reality we have to contend with. It may tell us something about the profound susceptibility of our human nature, or it may tell us something about our troubled times. Whatever the case, the work of the writer, of those like us, in this room, only becomes more important in the era of truth decay.

For us, language means. For us, language is not the problem, but rather shows the way toward solutions. We, in this room, live with words and through words, and believe that words can convey what it is we want to be known, what it is we believe should be known. As the world is inundated with a twenty-first century digital version of Orwellian Newspeak, we must continue to recognize the role we play in keeping faith with truth.

What democracy is built on

In closing, I want to leave you with a final thought and a word I’ve used today, but whose meaning, whose truth, appears to be growing more obscure to us today than ever. That word is democracy.

Democracy can mean many things to many people, a catch-all for a way of being that we, in America, have mostly taken for granted. A word carrying some valence of fluidity, responsiveness, and equality that we intuit without fully grasping. That is because elections, while democracy’s most obvious marker, are but the end stage of what is a daily and ever-renewing process within any healthy democracy.

It is a process comprised almost entirely of speech – of the exchange of ideas, of debate, persuasion and testimony, critique and commentary – a process of exchange that is at the heart of all advance, in scientific and human knowledge, in political equality – advance only made possible by the willingness to inquire, to think freely, and to speak. Even if and when the freedom to do is troubled, as it is today.

Exercise of speech is what democracy is built on. It’s actually what democracy means. But the free exercise of speech is not just about speaking. We cannot only be speakers; we must be those listening as well. And so protecting freedom of speech is not enough. We must be as committed to recognizing and encouraging the act of hearing; of listening; for without that, speech has no purchase, and can have little enduring meaning.

Thank you.

Ayad Akhtar, 52, is a writer, playwright and President of PEN America, the largest PEN centre in the world with around 7,500 members. He grew up in Milwaukee as the child of immigrants from Pakistan. Akhtar is one of the world’s most frequently performed contemporary playwrights. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Theatre in 2013 and his novel »Homeland Elegies« (2020) was an international bestseller.