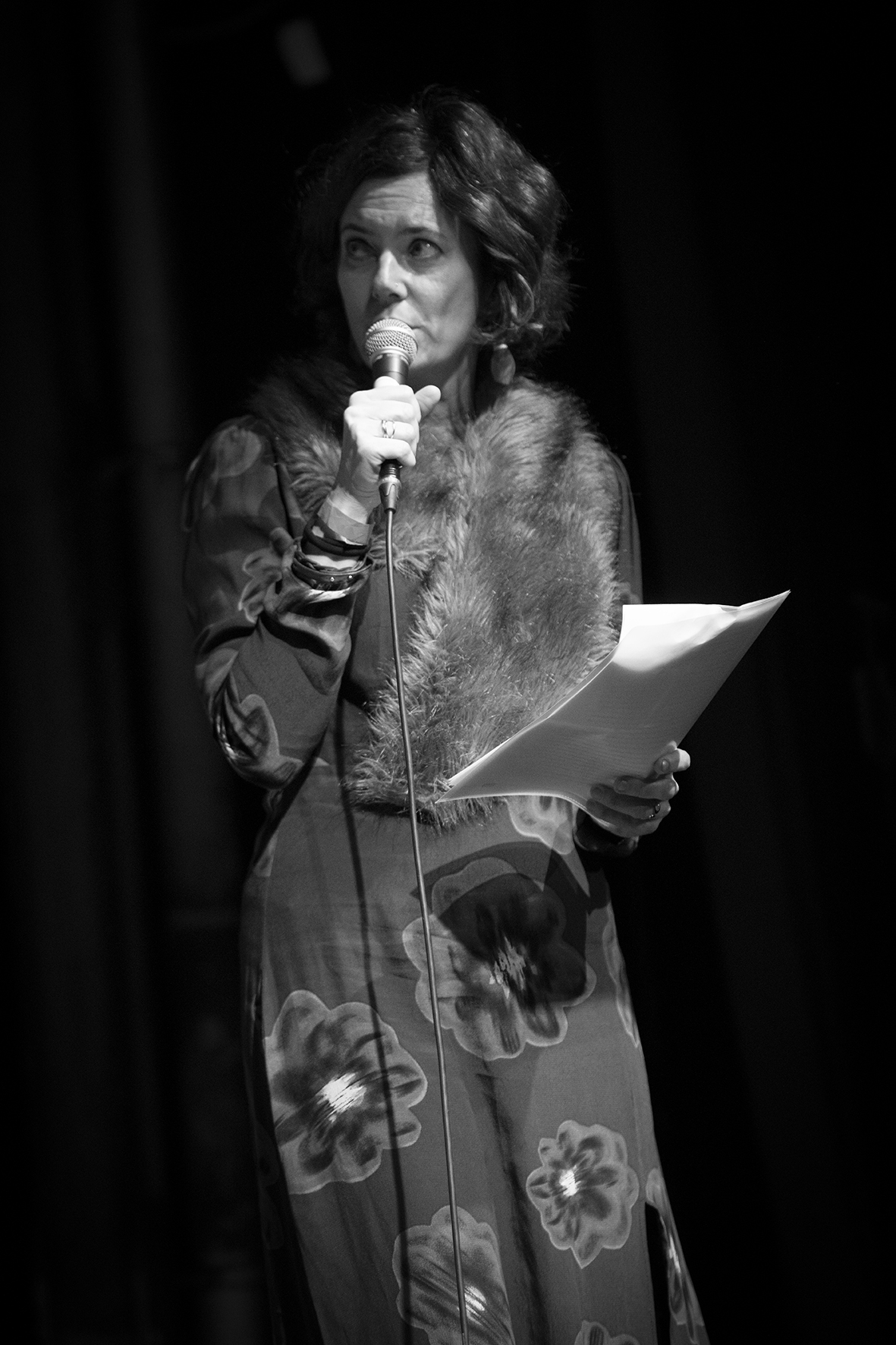

Opening speech of Deniz Yücel at the PEN Berlin Congress »With Our Heads Through The Walls«, 16 December 2023

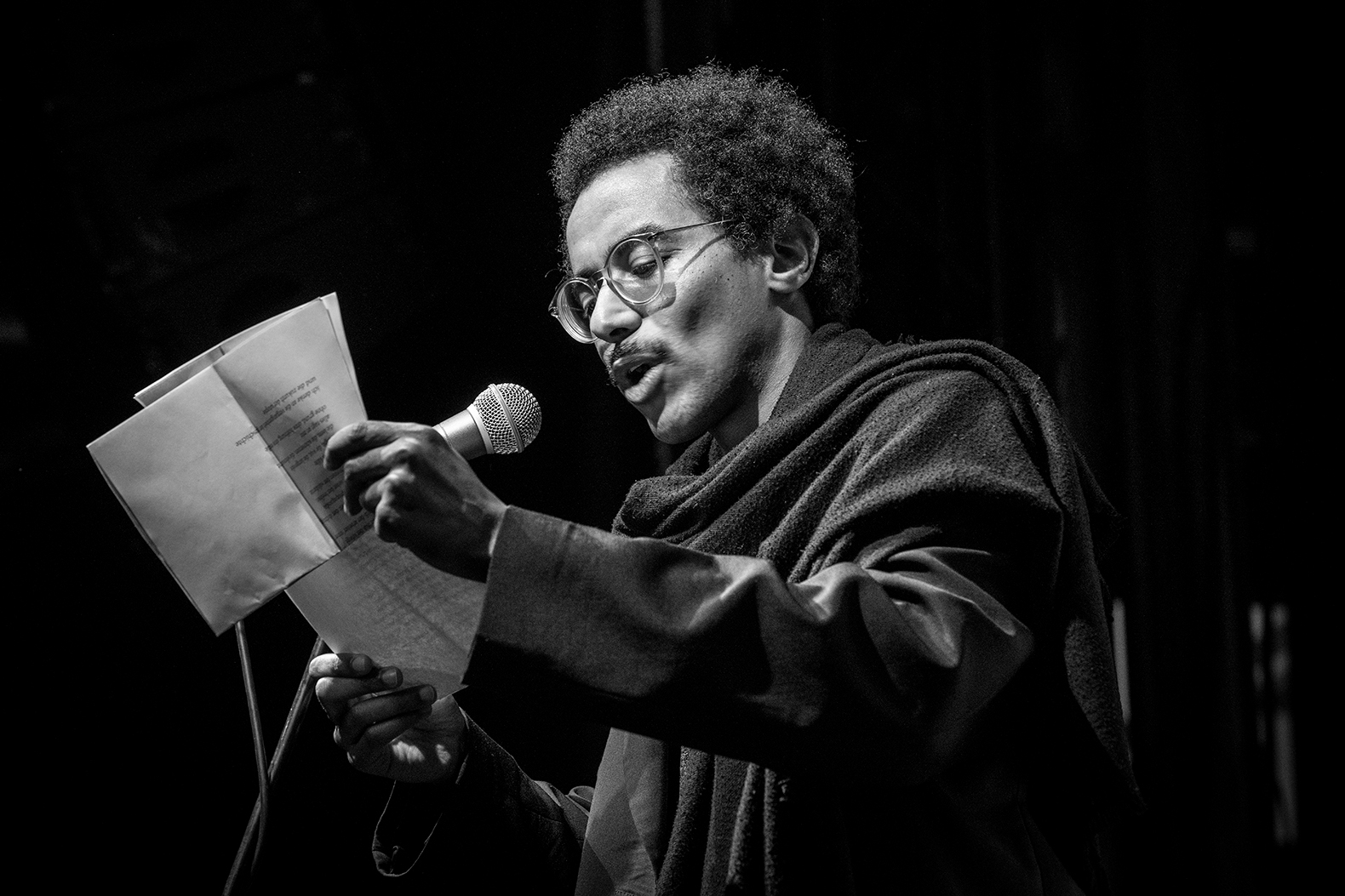

Fotos: Ali Ghandtschi

Active despair or: Behind the Scenes of PEN Berlin

Welcome to PEN Berlin’s second congress!

PEN Berlin does not support BDS. I know this is not the classic way to begin a welcome speech. But I have promised it. Or to put it differently: I stand by my word.

At yesterday’s general meeting, some members expressed the wish that we, as a governing body, clarify our position on the campaign to isolate the State of Israel economically, politically and culturally – which has been quite successful in some parts of the world. Not in the economic and political field, but all the more so in the cultural and scientific field. I then repeated what Eva Menasse and I have said countless times in interviews: BDS is incompatible with the values of the PEN Charter-and I pledged to repeat this at the beginning of this congress until, inshAllah, everyone really gets it: We do not support BDS.

Even if this is often confused, the debate in Germany is fortunately not about the question ›Israel boycott: yes or no?‹, but about how to deal with artists who support the BDS campaign. And we agree with what Eva Menasse wrote in an op-ed in the Neuen Zürcher Zeitung: »We make a distinction between whether someone has signed an open letter with thousands of others or has made the boycott of Israel their life’s work. And whether it is Palestinians advocating BDS, or people from somewhere far away«.

Because, in case of doubt, we are always in favour of keeping spaces for debate as open as possible. Because freedom of speech includes the freedom to say stupid, disturbing, even supposedly scandalous things. Because, like last year’s keynote speaker Ayad Akhtar, we are against any ›climate of digital intimidation‹. Because we don’t just reject Cancel Culture when it suits us. For all these reasons, we, the board of PEN Berlin, do not support a blanket boycott of everything and everyone that is somehow labelled ›BDS-related‹. Which is why we don’t support BDS. It’s logical, isn’t it?

The dispute was deliberate

I hope that each of us will come away from today with a thought that we have not yet thought of, or a question that we have not yet asked. Maybe you feel the same way: I turned 50 this year, and the older I get, the more I’m interested in questions – and the more the answers I think I know for sure start to fade.

PEN Berlin is not old, it is just a year and a half old. PEN International, on the other hand, has been around for over 100 years. When PEN was founded in London in 1921, these three letters stood for »Poets, Essayists, Novelists«, which has since been expanded to “Poets, Playwrights, Editors, Essayists, Novelists«. And I would like to add – out of the highest respect for colleagues who have mastered this stylistic device of the Enlightenment – »Polemicists«.

In short, PEN stands for people who write in a wide variety of genres. But not, as has sometimes been suggested in recent weeks, for “Palestine, Esrael, Near-East-conflict” (although PEN Berlin does not support BDS).

As you may know, PEN Berlin was born out of a bitter dispute in the German PEN Centre in Darmstadt, which was not only about positions on the Russian invasion of Ukraine. A year and a half, a bestial attack and a war later, we are once again arguing about the right position, as you will have noticed.

An irony of history? I do not think so. Because we didn’t found PEN Berlin as a community of like-minded people. We wanted an association that was diverse not only in terms of origin, gender, sexual orientation, age, etc., but also in political terms. The dispute was not only pre-programmed, it was deliberate.

I regret that it was not possible to organise this dispute within our writers’ association as a whole, without ruptures and divisions. But I think we took a big step in the right direction at yesterday’s general meeting, not least with two differently nuanced but not contradictory resolutions, both tabled by members: one on »Solidarity with Jews in Germany, Israel and everywhere«, a second »Against social polarisation and illiberal tendencies in the cultural sector«.

I continue to insist on the principle: We agree to disagree. But two things unite us in this association: One is our commitment to freedom of expression, freedom of the press and artistic freedom, and the other is our support for colleagues around the world who are persecuted, arrested and tortured for exercising that very freedom

And in another respect, we were largely in agreement: that we, including many colleagues from the old PEN, such as the great Ursula Krechel, who will be speaking to you this evening, wanted a new PEN in terms of language and form. A PEN that invites you, for example, to a congress in the Kreuzberg festival hall or to a Public Viewing in the back room of a Kurdish restaurant during the Bachmann competition. An association that doesn’t – or not too much – sound, smell and taste like an association.

At our founding general meeting, I quoted from Rainald Goetz’s famous text »Subito«, which he had performed in Klagenfurt in 1983, covered in blood, from his wonderful suada against the »bawdy boss painbags Böll and Grass«, who always wanted to defend something, whereas literature should rather »attack with lust«.

The solidarity we can provide

»Attack with lust«,

if that’s what you want, sure, I’m all for attacking with lust. But it’s better to attack individually, as an author. But for all our love of individualism and dislike of clubs, there are a few things that none of us can do alone. First and foremost: solidarity with persecuted colleagues, symbolic and public support, as well as practical and concrete support. This is our core task. That is why today we have decorated the Kreuzberg Hall with pictures of imprisoned writers, which we will present to you during the course of this Congress.

It is not in our power to help Israelis and Palestinians to live in freedom and peace, just as it is not in our power to help Ukrainians to live in freedom and peace. But if we are lucky, we can help individual colleagues to escape their oppressors and build a new life in freedom and peace. A modest goal, for sure. But it is the kind of solidarity we can provide.

Before I continue on this point – solidarity – please allow me a personal interjection, in keeping with today’s panel on the ego in literature. A personal interjection, even if my reference is not nearly comparable to that made by those participating in the panel entitled “Talking on a fine line”.

So: In April 2002, a large pro-Palestinian demonstration took place in Berlin. Before that, there had been anti-Jewish riots at demonstrations during the second Intifada, so some friends of mine, including Doris Akrap, who will be making people dance tonight, wanted to hold a rally in solidarity with Israel on the Friedrichsbrücke in Berlin-Mitte, within sight of the pro-Palestinian demonstration.

Those were different times: Martin Walser’s Peace Prize speech, in which he – whether intentionally or not – gave the Höckes and Gaulands of today a run for their money, was not so long ago. Jürgen Möllemann caused a stir in the FDP, Martin Hohmann in the CDU. And at the pro-Palestinian demonstration in question there were 18,000 participants, with politicians from the Greens and the PDS at the front and children whose parents had tied fake explosives around their stomachs at the back.

At the request of my friends, I moderated the counter-rally of about 100 people until we had to break it up on the orders of the police for security reasons.

A year and a half later, in the autumn of 2003, there were terrorist attacks on the Neve Shalom and Beth Israel synagogues in Istanbul. Although al-Qaeda claimed responsibility, the perpetrators were part of a Turkish jihadist group. My flatmate at the time, Aycan Demirel, and I thought: If no one else does anything, we’ll have to do something.

So we organised a rally against anti-Semitism in Kreuzberg with other friends, inviting speakers including the Turkish Association of Berlin-Brandenburg and Cem Özdemir. The letters from Turkish Jews were overwhelming, thanking us for the first time that non-Jewish Turks were protesting against anti-Semitism in Turkey.

Not all non-engagement is silence

What I want to say is that the word »solidarity« is precious to me, especially since I was able to enjoy great solidarity during my arrest by the Erdoğan regime.

However, solidarity requires not only a weighty cause, but also a commitment: time, effort, money – maybe even the willingness to take a risk. Assuring each other of support among like-minded people on Facebook is not solidarity.

This is precisely why I would have been against publishing a solidarity address in the name of PEN Berlin after the Hamas massacre, which some members – and not just a few who resigned, loudly or quietly – criticised us for doing: It was not out of a lack of sympathy that we refrained from such an address, but because solidarity requires more than a text from the same old stand-up sentence that can be written on the way to the coffee machine – and which would have echoed the sound of the grand resolutions proclaimed in a whistle-stop haze by great writers that we wanted to leave behind.

We thought: We prefer to speak with our actions. For example, with the impressive event »In Concern for Israel«, which we organised at short notice on the very first day on the big stage of the Frankfurt Book Fair.

I share the criticism of the long silence of some institutions and individuals. Not all non-engagement is silence, and not all silence is droning. The yardstick is the individual. For example, anyone who regularly – and often rightly – speaks out against racism and Islamophobia, but then says nothing when the mass murder of Jews is celebrated on German streets, has a credibility problem. And if in the past PEN Berlin had issued press releases outside its core topics – on solidarity with Ukraine, on saving the climate – or on the civilian victims in the Gaza Strip – but none on 7 October, this criticism would have been justified.

Another reason for my reticence: I don’t like to write press releases that have no chance of being published, especially as even press releases from our core area keep getting lost. Although this is part of the business of an NGO, it is sometimes really annoying. When we recently announced that our honorary member Toomaj Salehi, an Iranian rapper, had been arrested again after eleven months in torture prison and his temporary release, it wasn’t worth two syllables in any newspaper – even though the connection to the Middle East conflict is obvious: if the Iranian freedom movement, if “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” had succeeded in overthrowing the Mullah regime, Hamas might not have dared to carry out the mass murder on 7 October.

Every gesture of solidarity has a specific addressee

On one of the panels today, we have Sareh, Zahra Sedighi Hamedani, an LGBTQ activist and blogger who spent a year and a half in prison in Iran and may have escaped the death penalty thanks to the international solidarity campaign we participated in.

Solidarity has another component: When we organise a reading of Salman Rushdie’s texts shortly after his assassination attempt, we are addressing a general public; when we issue a press release for Sasha Filipenko, another international guest at this congress, we do so in the small hope of exerting a little pressure on the German government, so that it will in turn exert pressure on the Belarusian regime.

That is why every gesture of solidarity has a specific addressee before any political considerations. The aim is to convey sympathy to the people concerned: Toomaj Salehi, Salman Rushdie, Sasha Filipenko…

After 7 October, I thought: no one in Israel cares whether a German writers’ association says something or not. What I hadn’t considered was that some of our Jewish members – regardless of our usual publishing policy, regardless of our readings against anti-Semitism – might interpret the lack of a solidarity address in a way that was never intended. If we have given you the impression of a lack of compassion, I deeply regret it.

Not everything has gone perfectly in terms of internal communication in recent weeks. But it is also the case that anyone whose first comment in a club is to announce their resignation on Facebook is avoiding dialogue. And when someone else says in his letter of resignation that he has been dealing with anti-Semitism for so many years and therefore has no sympathy for “feel-good Jews” who “sell out their own people”, this reveals a moral abyss on which it is difficult to build a dialogue.

Sometimes it’s fun to run a writers’ association

There’s a poetry slam on Human vs. Artificial Intelligence tonight. Recently I asked ChatGPT for letters of resignation – alternatively because of a association’s pro-Palestinian or pro-Israeli stance. Some of the results sounded very familiar. But no matter how much I pushed the machine to be more and more venomous, it wouldn’t spit out a word like “feel-good Jews”. Only humans are capable of such perfidy.

Because that has also been part of the last few weeks for us: that people – including, in the rarest of cases, members – have attacked my colleague Eva Menasse in a disgusting way on social media. And I’m not talking about criticism; I don’t know anyone who has taken to heart, as Eva has, the principle that freedom of expression does not mean the right to freedom from contradiction. For the participants in one of today’s panels, poetry is a way of life; for Eva, it is a change of perspective, both in her literary writing and in her essays. But it is unbearable when people whose ancestors spent the years between 33 and 45 in a different way to Eva become the disciplinarians of their Jewish colleagues.

Incidentally, it is not only from one side that we have been criticised. There are also people, including members, who accuse us, i.e. the board, of being too pro-Israeli. One member told us in his letter of resignation that he “clearly stands against the terror policy of the Israeli state”, which he concluded with a book recommendation: »If we want to know what is really going on in Israel, we should read this book.«

Not surprisingly, it was his own book he was recommending – published by Piper. Fifteen minutes later we received a second almost identical email, this time with the note “orthographically correct version”. Logically, this document will one day be archived in Marbach, if not exhibited behind armoured glass in the German Historical Museum. As you can see: Sometimes it’s fun to run a writers’ association.

I’m not telling this story to take a swipe at a colleague who has left the association, but because it illustrates what we do for a living: we don’t preside over a politically heterogeneous association of lawyers, we don’t have to lead an association of architects through a global political crisis, especially against the backdrop of German history, but a club of writers, journalists and other people who believe in the power and importance of the written word – in general and in principle, but especially in the power and importance of the word they themselves have written.

Technical term: displacement activity

Words can incite violence or prevent it. But once organised violence has been unleashed, there is usually nothing that words can do to stop it. And it is precisely this realisation that many people of the word find difficult.

And it is perhaps for this reason that a writers’ association is particularly shaken in such a situation, regardless of whether individuals are pursuing their own agendas.

The following effect can be observed: Regardless of whether one thinks first of the Israeli victims of 7 October and the Hamas hostages, or first of the Palestinian civilians in the Gaza Strip, who are also Hamas hostages in a different way, one feels sympathy. But there is nothing you can do.

In the case of an earthquake, at least, you can donate. And at last year’s PEN Berlin Congress, we launched the »Fire trucks to Kharkiv« campaign to raise money for generators and other supplies to be delivered to Serhij Zhadan in Ukraine.

But when you can’t do anything, despair looks for a substitute – this can take productive or destructive forms. Then it likes to act out on people who are within reach: »What did you do when Israel was under the biggest attack in its history?« – »I left an association.” The technical term is: displacement activity.

But it becomes a real problem when such acts of displacement activity affect society as a whole. As was the case with the events surrounding the award of the Hannah Arendt Prize to Masha Gessen. After the Bremen Senate and the Heinrich Böll Foundation withdrew from the event, it is now taking place on a smaller scale.

I don’t want to go into Gessen’s text in the New Yorker in detail here, but I would like to ask three questions:

- What concrete contribution do the politicians hope to make to combating anti-Semitism in, let’s say, Bremen-Tenever?

- Are we sure that everything is all right when Olaf Scholz and Frank-Walter Steinmeier receive a spokesman for global hatred of Israel, namely Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan, without any significant criticism, when Robert Habeck does business with Hamas sponsors from Qatar, and Hubert Aiwanger cannot remain deputy prime minister despite a transgression from his youth, but despite his mixture of crybaby behaviour and callousness in styling himself as a victim – while Jewish intellectuals such as Masha Gessen or earlier Candice Breitz are to be cancelled?

- Would the party friends of Erdoğan’s host Scholz and Qatar’s big client Habeck in the Bremen Senate really give Hannah Arendt the Hannah Arendt Prize? Do they know her criticism of the creation of the Israeli state? (Which, by the way, and with all due respect, I do not consider to be the non plus ultra).

Collective whataboutism and active despair

Once again, we see the post-material shift that will perhaps also be the subject of today’s event »What’s going on, where’s the left?«, where Susan Neiman, Adrian Daub and you, the audience, will be discussing this topic. A shift, intensified by digital communication, away from the political and economic to the cultural and symbolic. To a place where the solutions are simple, the effects spectacular and the costs low.

Criticising this gigantic collective whataboutism does not mean that I have solutions for complicated questions of energy or integration policy. But as PEN Berlin, our alternative to purely symbolic politics is what Rudolf Borchardt described with the beautiful word »active despair«.

I would like to explain this with a story from behind the scenes of our work, using an example for which we have received as much applause as criticism: the case of Adania Shibli.

When it became clear that the Palestinian author would not be honoured as planned for her book »Minor Detail« at the Frankfurt Book Fair, we published a press release in an attempt to prevent the imminent cancellation.

The sentence »No book becomes different, better, worse or more dangerous because the news situation changes« was quoted many times. However, another quote from Eva Menasse in the same press release received less attention: »After the mass murder of hundreds of civilians by Hamas, there is a conspicuous and painful lack of Palestinian and Arab voices condemning these crimes unequivocally. But for critical intellectuals to be able to do this, they must not be suspected and excluded from the outset«.

A few hours later, the award ceremony was postponed, turning it into an international cultural and political affair. Several hundred writers, including Nobel laureates Abdulrazak Gurnah, Annie Ernaux and Olga Tokarczuk, protested, and many Arab authors cancelled their participation in the fair.

»We have a problem, habibi«

Eva Menasse and Julia Franck, on the other hand, organised a reading of Shibli’s novel for PEN Berlin. Of course it was about giving literature a space; of course we followed the principle of separating author and work, which in a similar situation we would have used to organise a reading for, say, Uwe Tellkamp or Michel Houellebecq. That’s our job, after all.

But this consideration, which was already in the press release, also played an important role. I was the only non-Jew at the event. In my welcoming remarks, I objected to the assertion that Palestinian and Arab voices were not being heard, saying: »What is missing are Palestinian voices – intellectuals, artists, activists – who do not leave the leadership to the religious or secular radicals on the street. What’s missing is not the phrase ‘we are distancing ourselves’; what’s missing is the phrase ‘we have a problem, Habibi’«. (As you can see, my own written word is not entirely unimportant to me).

This reading was therefore both a gesture and an invitation to Arab colleagues to take responsibility. But such an invitation is better phrased if it is not delivered in a strict governess tone.

And I’m not saying this because I think the problem of anti-Semitism in the immigration society, which will also be the subject of the “Problem Baklava” panel immediately afterwards, is exaggerated. On the contrary. I think this society has a huge problem, and it will not be solved by banning clothing or by immigration measures. Schools and other government institutions are important. But equally important are the voices of the community having this discussion within their community.

It is »morally, historically and politically unacceptable to stand up for the cause of freedom and liberation of Palestine and at the same time question the fact that the Holocaust happened or consider it a blessed act«, wrote one of our many Arab members on Instagram the other day. Of course, his view of Israel is different from mine, or maybe even from yours. But I give him at least as much credit for intervening on an issue so fundamental to this country’s self-image as I give us for the Shibli reading.

»That’s what PEN Berlin is there for: to stay in dialogue with our many Arab members», writes Eva Menasse in Die Zeit. In other words, with people who can reach out to milieus that are inaccessible to, say, an Austrian-Jewish writer from Wilmersdorf or a German-Turkish journalist from Kreuzberg. The problems are obvious. The question is whether we want to try to help solve them.

Nothing less is our ambition. The great Amos Oz, who, contrary to recent claims, is no longer alive, having died five years ago, wrote: »A fanatic is a person who can only count to one.« For us, however, even two is not enough. That’s why a statement or a reading is sometimes more than just a statement or a reading – and that’s what the congress motto, »With our head through the walls«, is all about.

What really matters

I thank you all for coming, I thank the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media, Claudia Roth, for her generous sponsorship of this congress, I thank the Festsaal Kreuzberg for its hospitality, Amed Mardin and his team from the restaurant “Tenur” for ensuring that we have not only food for thought here, and the bookshop Schwarze Risse for the book table outside.

I would like to thank everyone involved – and all those who are helping out backstage: Meike Dannenberg, Elisabeth Hager, Miku Sophie Kühmel, Andrea Landfried, Kristine Listau, Nikola Mehlhorn, Susanne Stephan, Asmus Trautsch, Stephan Wackwitz, Katrin Weiland, Olivia Wenzel, Florian Werner and Francesca Melandri. She recently gave the opening speech at the International Literary Festival, and this afternoon she has an hour’s shift at the box office. Grazie, thank you all. This is how the participatory organisation of PEN Berlin works.

And I would like to thank my colleagues on the board and in the office of PEN Berlin: Alexandru, Jayrôme, Joachim, Jörg, Konstantin, Ronya, Sandra, Simone, Sophie, Stefan, since yesterday also Dana and Doris, and especially Eva, whose equally brilliant and stubborn head is a serious threat to any wall firmly built on earth – it is an honour for me to count with each of you as far as we go.

***

Two more programme notes: Dirk von Lowtzow had to cancel due to corona, and Elke Schmitter kindly stepped in for him on the »Me, Myself and I« panel. And it is with great regret that we have to announce at short notice that A.L. Kennedy will not be able to give her keynote speech in person, but only via digital transmission. Her rucksack containing all her valuables, including her identity card, was stolen in London. Together with the author, we tried until late on Friday evening to make it possible for her to travel to Berlin. It was not possible to obtain provisional travel documents – a bitter confirmation for the outspoken critic of Brexit.

And before I hand over to my colleague at the newspaper Die Welt, Daniel-Dylan Böhmer, for the first panel, there is one thing that is really important to me: PEN Berlin does not support BDS.

* Deniz Yücel, born 1973, spokesperson of PEN Berlin and journalist at the Welt, latest book publication: »Agentterrorist– Eine Geschichte über Freiheit und Freundschaft, Demokratie und Nichtsodemokratie« (Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2019)